- Home

- James Blake

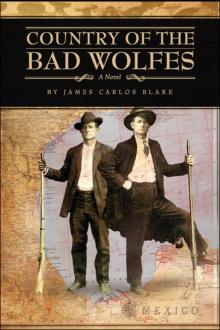

Country of the Bad Wolfes Page 5

Country of the Bad Wolfes Read online

Page 5

He came to awareness under a sky of iron gray. A young woman was crouched beside him, studying him with curiosity. She wore an apron and held a broom and had a white crescent scar at the outer corner of one eye. She asked if he were wounded. He said he didn’t think so. His voice sounded to him like a stranger’s. He tried to get up but fell back and nearly passed out again. She put the back of her hand to his cheek and then a palm to his forehead, then said she would be right back.

In her absence he was unsure whether she had been real or imagined. But then she returned, accompanied by a grayhaired man with a black eye patch. They helped him to stand and steered him a short way down the sidewalk and into a small café cast in soft yellow light and infused with the aromas of coffee and sausage and cinnamon. There were tables covered with white cloth and a small bar with a few stools. Samuel Thomas was unsure if he in fact apologized for his stink or if he only thought he did. Then nearly took the girl and old man down with him as he fell in a swoon.

He awoke on a cot in a dimly lighted storeroom. The sole window was small and high and the daylight in it was as gray as he’d last seen it. An oil lamp with its wick set low burned on a small table beside the cot. The air pungent with peppery odors. The walls were hung with cookware, the ceiling with strings of dried sausages and chiles, the shelves held condiments, sacks of sugar and salt and maize and wheat flour. There were casks of beer and cases of bottled wine. In a corner of the room, a rat lay with its neck under the sprung bail of the trap, its eyes like little pink balloons and the cheese white in its mouth. Samuel was under a blanket and wearing a night shirt. He only vaguely recalled someone undressing him, washing him with a warm cloth, holding a glass to his lips. A wonderful liquor of a kind he had never tasted before.

He’d been awake but a few minutes when the door opened slightly and the girl looked in and saw his open eyes, and smiled. She went away and a few minutes later came back with a tray of food and set it on the little bedside table. She said he had slept around the clock. He guessed her to be a few years older than himself.

She put a cool palm to his forehead and smiled. Your fever is nearly gone, she said in the clearly enunciated Spanish of those educated in the capital.

She leaned down to take a look into the chamber pot under the bed. She said that she had at first feared he had eaten something spoiled or drunk bad water, but had since decided he was not poisoned, only malnourished. A few days of rest and proper feeding, she told him, and he should be fine.

She helped him to sit up. On the tray was a steaming bowl of the tripe stew called menudo, seasoned with lemon juice and chopped green chile, and a small plate of white rice topped with a fried egg. He felt he could feed himself but did not object when she sat on the edge of the cot and began spooning the menudo to him. She said her name was María Palomina Blanco Lobos. The one-eyed man was her grandfather Bruno Blanco. He owned the café, La Rosa Mariposa, and she had been helping him to operate it since she was a child. They lived in an apartment upstairs and had no family but each other.

The food was delicious but he could not finish half of it before he was sated. She said it was an excellent sign that he had any appetite at all. He asked if he might have some of whatever it was they had given him to drink before. A French brandy, she told him, then left the room and returned a minute later with a small glass of the reddish liquor. He sipped from it and felt its sweet burn down his throat.

He asked why they were being so kind to him. Did they take in every man they found lying on the sidewalk?

Of course not, she said. It was the mark on his face. She knew what it meant. She and her grandfather had read about the San Patricios in the newspapers. Bruno Blanco too had once been a brave fighter, in the long war for independence begun by the great Father Hidalgo. Even after he saw Hidalgo’s severed head on display at Guanajuato, Bruno Blanco had continued to fight against the brute Spaniards until independence was won. That was how he lost his eye, in that war.

But I still do not know your name, she said. “Como se llama?”

“Samuel Tomás,” he said.

Are you Irish?

No, he said.

“Ah pues, eres americano.” She smiled.

Not anymore, he said.

She seemed puzzled by that but let it pass. “Tomás no es su apellido, verdad?”

No, he said, his family name was Wolfe.

“Wooolf,” she said, trying it on her tongue. Then asked why he smiled.

He asked if she knew what the name meant.

No. What?

“Lobo.”

“En verdad? Lo mismo como la familia de mi mamá?”

Well, not quite the same. For one thing, her mother’s maiden name was in plural form—Lobos—but his name was not. Also, his surname had an “e” on the end. “En inglés no hay una ‘e’ en la palabra para el lobo.”

Even so, she said, the coincidence of their family names was a little curious.

He said he supposed so.

Where had he learned to speak Spanish?

Everywhere between Matamoros and Mexico City.

Well, she said with a smile, she did not mean to be rude, but it sounded like it. His grammar was good, but that accent! It had to be the only one of its kind in Mexico.

He returned her smile. The brandy warmed him. He asked about the scar and she said she’d got it from a fight with a ratero who stole her purse on the street about a year ago. Some weeks after, she and her grandfather were shopping in the rowdy Volador Market behind the zócalo when she spotted the thief in a packed crowd in front of a kiosk, watching a puppet show. Bruno Blanco asked if she were absolutely sure, and she was. Her grandfather had then eased through the crowd and up alongside the thief and so neatly stabbed him in the heart from behind that he was dead without a cry. As her grandfather withdrew from the crowd, the man sank in the press of people around him without drawing more than a glance of irritation at one more drunk passing out in public.

Your grandfather is an honorable and capable man, but I would have made the bastard look at you before I killed him. So he would know why he was getting it.

She studied his eyes. I believe you.

You have beautiful skin.

She blushed even as she laughed at his sudden compliment. Then held out an arm for his inspection and said, “Leche teñida por un poquito de café.” Her family had been Creole until Grandfather Bruno married a mestiza. It was that grandmother who put the trace of milk-and-coffee in her complexion.

Had she ever been married?

No, but she had been engaged to an army officer when she was sixteen. He was sent to Sonora to fight Yaquis, and a month before he was due to return for their wedding he took an arrow in the leg. The wound became infected and the leg had to be cut off. He wrote her a letter saying he would understand if she decided not to marry him now that he was an incomplete man. She wrote back to tell him not to be foolish, that she didn’t care if he was without a leg. But the infection had poisoned his blood and by the time her letter got to the military hospital he had been dead almost a week.

Did you love him very much?

Yes. But now I cannot clearly remember his face.

You have no picture of him?

No. From her apron pocket she produced a black cigarillo and set it between her teeth, then rasped a lucifer into flame and put it to the end of the little cigar. The smoke was blue and sweet. The only women he’d ever seen smoke were some of the girls of the Blue Mermaid and some women of the Mexican outlands. He was taken with her easy confidence. She smiled and asked if he wanted a puff, then held the cigarillo to his lips. It was moist with the touch of her tongue. The act seemed to him somehow more intimate than any he had ever shared with even a naked woman.

She closed her fingers around his clawed hand and said, Listen. And told him that even after she saw the brand on his face she had been in doubt of what to do. She had thought to leave him on the sidewalk to recover on his own or to die, whichever way fate woul

d have it.

It was like a little trial in my head, she said. One side argued that I should help you because you fought for my country and the other side said not to be foolish, life in this terrible time is dangerous enough without bringing a stranger under our roof, especially a foreigner. A man who has killed so many might choose to kill us too for whatever reason enters his head. And then you opened your eyes. When I saw them it was decided. You have true eyes.

He said he was glad the verdict went his way. He would have hated to become one more corpse for the dead wagon to collect.

You are luckier than you know, she said. I was decided before I saw you smile. I do not mean to insult you, but with that hole in your teeth and the way that scar pulls your face, it is not the kind of smile to make others smile back. If I had seen you smile before deciding about you . . . well, who knows what the verdict might have been.

She laughed. And his grimace of a grin widened.

He accepted Bruno Blanco’s offer of employment as the café’s barman, a job he could do with one good hand and one bad one. He could live in the storeroom, old Bruno said. He had been there a week when she tiptoed down the stairs in the middle of the night and slipped into his cot. After a month of it, Bruno Blanco said they should stop thinking they were fooling anyone and might as well live together in her room with the larger and more comfortable bed. In the darkness of their trysts she had shed silent tears as her fingers traced the whip scars on his back, and when she saw them in the lamplight she cried harder yet and cursed the whoresons who had given them to him. Cursed all armies of the earth as gangs of barbarians.

They had been together only two months when she proposed marriage because she wanted children. But if you do not want to be a father, she said, we can continue as we are. You are my first importance. And because there was nothing he wished to do with his life other than what he was doing, nowhere he wished to be other than where he was, he could think of no objection to marriage or fatherhood and so said all right.

They never spoke of love. She would in time tell him that she had never had a better friend, but he knew it was not true, knew her grandfather had been a better friend to her than anyone else could ever be. But she did not know he told the same lie, for she was unaware of his brother. He had told her he was an orphaned only child. He lied for no reason but to keep things simple, and he assumed she did too.

But he had not lied about no longer regarding himself as an American. When they married in January he renounced his Anglo surname and took her family name for his own. María Palomina Blanco y Blanco was congratulated for her marriage to a gallant defender of Mexico, a man the more noble for his greater allegiance to justice than to birthplace. Old Bruno beamed with pride in his fine grandson-in-law.

So. He entered a life of daily routine that called for no hard decisions and required no plans and demanded no accounting of his past. He was an able bartender, efficient and circumspect, and as the job called for more listening than talking, it suited him well. The place catered to a respectable patronage, most of it neighborhood shopkeepers and residents, regular customers of long standing. Their gazes at his brand were mostly discreet, and he was never questioned about the war that gave it to him.

He had told María Palomina of his liking for the hornpipe and having been taught to play it by his grandfather, and she one day spied one in a pawnshop window and bought it for him. He found he could clutch it well enough with his clawed hand while the fingers of his good one worked the note holes. She clapped and shouted “Bravo!” when in spite of his bad hip he managed a few hobbling steps of a sailor’s jig as he played a tweedling tune.

He acquired the habit of a daily walk around the neighborhood before lunch, but never went farther than three blocks in any direction. Whenever he approached that outer boundary he got a hollow feeling in his stomach, a peculiar sensation that if he went any farther he would have a hard time finding his way back. It was not something he could fully explain even to himself and he would never even try to explain it to anyone else.

His enduring pleasure was drink. Every night after the café closed he would sit at the bar with a bottle and glass for another few hours, on occasion until nearly dawn. María Palomina sometimes joined him for a drink or two and sometimes old Bruno as well, but usually they left him to imbibe by himself, as they sensed he preferred to do. He was a quiet drunk and a tidy one, never clumsy or impolite, and possessed a constitution that well tolerated hangover. If María Palomina ever wondered what thoughts he kept in those late inebriate nights, she never asked. Had she done so, and had he answered truthfully, he could only have said that he was fairly sure he thought of nothing at all, and when he did think about things, he could never remember them the morning after, nor tried very hard to.

Their first child, Gloria Tomasina, was born the next winter, and a year later came Bruno Tomás. The year after that saw the birth of Mariano, who lived but six days. A month after the infant’s funeral their grief was enlarged when Old Bruno died in his sleep. Their last child, born in the summer of 1853, they christened Sofía Reina.

DARTMOUTH DAYS

John Roger had not really expected Samuel Thomas to post a letter to him from every port as he had promised, but as winter gave way to the first muddy thaw of spring he was sorely disappointed not to have received even a note from him in the six months since they’d last seen each other. He was expecting him to appear in Hanover any day now, perhaps with explanation for his lack of correspondence, perhaps with no reference to it whatever. In either case, he knew his brother would be smiling and full of confidence and have stories to tell, and knew that his pique toward Samuel Thomas would not withstand the pleasure of seeing him again.

Then the trees were greening and beginning to bloom, and he completed his freshman final examinations—and still there was no word from Samuel Thomas. And now he began to be worried.

He wrote to the Portsmouth harbormaster’s office, inquiring after the Atropos, and was informed the ship had been delayed on its return voyage, incurring damage in a storm off Cape Hatteras. The vessel had been under repair for weeks before again setting sail, and it was now due to make Portsmouth in the middle of June. John Roger was relieved but also vexed. How much effort would it have taken for Samuel Thomas to write him a note about the delay? He had planned on going to Portsmouth to greet him at the dock but now thought he might rather accept the invitation of some college friends to spend a few weeks in Boston. Let that thoughtless blockhead do a little worrying of his own when he didn’t find him in Hanover.

But on the sunny afternoon the Atropos landed in Portsmouth, John Roger was there to meet the ship. And found out from one of its officers that Samuel T Wolfe was not among the crew and had in fact not reported for duty before the ship left Portsmouth in August. All John Roger could think to say was, “I see.”

He walked along the waterfront for a time without a coherent thought, then halted and looked about him like a roused sleepwalker. Then made directly for the Yardarm Inn where he and Sammy had quartered the previous summer. The desk man consulted a register and said that a Samuel Wolfe had been living there at the end of August, all right, but had quit the premises in debt of a day’s rent. The date of his arrears coincided with John Roger’s departure for Hanover. If he’d left any possessions they had been sold or discarded.

John Roger then went to the office of the city graveyard and pored over its registries. Then to the local hospital, where an administrator carefully examined its record of patients. In none of those pages was entered his brother’s name. Over the next weeks he went to every jail and prison fifty miles to the north and south of Portsmouth. In Boston the jail clerk ran his finger down the inmate ledger and stopped at a name and looked at it more closely. “Ah yah,” he said, “Samuel Wolfe, right here he is. And don’t I remember him now?” He peered over the rims of his spectacles at John Roger, whose pulse sped. “But grayhaired he was and black in the teeth with his sixty years and more, so I don�

��t suppose he was your brother, now was he?” John Roger said, “Damn it!”—and received a severe look and stern reminder that he was in a Boston municipal office and not in some waterfront public house and such profanity could get him ten days in one of the cells down the hall.

He was at breakfast in a café when it occurred to him that Samuel Thomas may have contracted amnesia by some means and be wandering about with no inkling of his own identity. Perhaps right there in Boston. For the next three days he scoured the city streets before conceding the impossible odds of finding him by this haphazard means. Then admitted the desperate foolishness of thinking Sammy could be amnestic. Unable to think of what else he might do, he returned to Hanover.

He lived in a small and Spartan room near the campus, his scholarship not providing for dormitory lodging. He lay awake deep into the nights, his imagination amok and returning again and again to the grim possibility that Samuel Thomas had been killed in some hideous accident or taken fatally ill, his unidentified remains consigned to a pauper’s grave. Or had been murdered while being robbed, or in some street affray, and his body pitched into the river or the sea or the city refuse pit to be burned with the waste. He could conceive of no other explanations for his brother’s disappearance and lack of communication. He spent part of every day staring at their graduation picture.

The summer was waning into its last weeks when he awoke one morning with the sure conviction that Samuel Thomas was dead, and that he may have been dead since their first night apart. Dead all that time that he had so blithely thought of him as alive. He could hardly draw breath against the crushing sensation of his loss, his overwhelming aloneness. “Oh God, Sammy!” he said. Then wept with such force he ruptured a blood vessel in his throat. Which became infected, then worsened, then prostrated him with a raging fever.

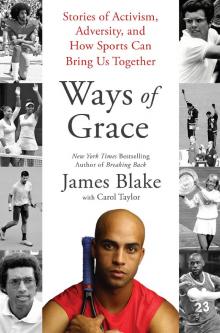

Ways of Grace

Ways of Grace The Widow Bereft

The Widow Bereft Country of the Bad Wolfes

Country of the Bad Wolfes