- Home

- James Blake

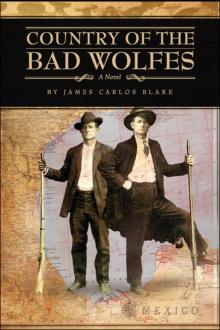

Country of the Bad Wolfes

Country of the Bad Wolfes Read online

Country of the Bad Wolfes

James Blake

The violent but manifest destiny of the Wolfe family from Yankee America through the Diaz Regime of Mexico.

COUNTRY OF THE

BAD WOLFES

A Novel

BY JAMES CARLOS BLAKE

CINCO PUNTOS PRESS EL PASO, TEXAS

Country of the Bad Wolfes :A Novel.

Copyright © 2012 by James Carlos Blake.

All rights reserved.

IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER,

CARLOS SEBASTIÁN BLAKE

(1911-2002)

OTHER WORKS

BY JAMES CARLOS BLAKE

The Killings of Stanley Ketchel

Handsome Harry

Under the Skin

A World of Thieves

Wildwood Boys

Borderlands

Red Grass River

In the Rogue Blood

The Friends of Pancho Villa

The Pistoleer

Therefore, since the world has still

Much good, but much less good than ill,

And while the sun and moon endure

Luck’s a chance, but trouble’s sure,

I’d face it as a wise man would,

And train for ill and not for good.

—A. E. Housman, A Shropshire Lad

We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us.

—PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON , Magnolia

What country more dear or defiant than that of our own blood?

—ANONYMOUS

No hay reglas fijas.

—A PRECEPT OF LONG STANDING ALONG THE LOWER RIO GRANDE

PROLOGUE

The family landed in the Western Hemisphere in the person of Roger Blake Wolfe, who arrived with a price on his head. No likeness of him—a sketch, a painting, a daguerreotype—survived through the generations, and the accepted description of him as handsome was based solely on the family’s penchant for romantic fancy and the genetic testament of their own good looks. Even his own sons never knew him in the flesh.

As a matter of record, Roger Blake Wolfe was born in London in 1797. His father was Henry Morgan Wolfe, an Irishman of murky lineage who triumphed over that disadvantage of birth to become a British naval officer and then managed the even more heroic achievement of marrying into a wealthy Knightsbridge family named Blake. Henry Wolfe had high ambitions for his son in the Royal Navy, but Roger, who loved the sea but abhorred regimentation, did not share them. When he ran away at age sixteen, absconding from a maritime academy, his father disinherited him through an announcement in the Times.

Thirteen years later Roger Blake Wolfe was a pirate captain of some notoriety, one of the last of a breed near to extinction by the early 19th century. His ship was named either the Yorick or the York Witch, the former name appearing in some reports and court documents, the latter in others. Although he restricted his freeboot to the waters off Iberia and West Africa and never attacked an English vessel, the British in 1826 acceded to diplomatic imperatives and joined with various aggrieved nations in posting a reward for his capture, dead or alive. Whereupon Captain Wolfe decided to distance himself from that part of the world. Three of the crew’s Englishmen chose not to go with him and he put them ashore near Lisbon with enough money to make their way home. The first mate said he understood their feelings. He said it was a hard thing to say goodbye forever to one’s home country. Captain Wolfe laughed at that and said it wasn’t so hard when one’s home country wanted to hang one. And set sail across the Atlantic.

Fifteen leagues shy of Nantucket the ship was struck by a ferocious storm and foundered. Only Roger and two of his crew survived the sinking, clutching to a spar in that plunging frigid sea. The storm at last abated during the night but one of the crewman succumbed to the cold and slipped off into the darkness. Shortly afterward the spar suddenly shook in a phosphorescent agitation and the other crewman vanished, his scream lost to the depths. Roger did not see the shark that took him. Through the rest of the night he expected to be attacked too but was not. The following day broke clear and sun-bright on a calm sea, and by wondrous chance he was spotted by an American whaler bound for home. His fingers had to be pried from the spar and it was hours more before his shivering began to ease under a heavy cover of blankets and sizable doses of rum. He was landed in New Bedford and his adventure condensed to a newspaper item in which he claimed to be Morgan Blake and described the lost ship as a Dutch cargo carrier.

It is anyone’s guess how he occupied himself during the next year or what took him to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where in October of 1827 and under his true name he married Mary Margaret Parham, who at the time believed he was a merchant ship master. Six weeks later he sailed away to southward and she never heard from him again. Six months after his departure she bore his twin sons. The boys were a year old when she received notice of their father’s execution in Mexico.

Archives in Veracruz contain a variety of documents pertaining to Roger Blake Wolfe’s arrest in a waterfront cantina on Christmas Eve of 1828 and his ensuing trial and conviction on charges of piracy and murder in Mexican waters. In keeping with protocol, the British Consulate provided a Mexican attorney for his defense and afterward concurred with the court’s verdict. For reasons unrecorded he was sentenced to be shot rather than hanged, the usual and more ignominious fate of condemned pirates.

The morning of his execution on the first day of February, 1829, was reported to be clear and mild. The central plaza raucous with parrots and marimba bands, with vendors hawking melon slices and coconut milk. The air tanged with the smell of the gulf. The large crowd was composed of every social class and in a mood even more festive than usual for an execution—perhaps, as one newspaper surmised, because of the novelty of the condemned man’s Anglo nationality. When Roger was trundled to the plaza in a donkey cart amid the tolling of steeple bells and made to stand against the church wall in front of the firing squad, there were catcalls and whistles but also much comment on his undaunted demeanor and striking figure. His clothes were fresh-laundered, his beard in neat trim, his hatless black locks tied in a horse tail at his nape.

A diversion occurred when a pair of young women at the fore of the crowd, each claiming to be Captain Roger’s true sweetheart, got into a skirt-hiking scuffle to the delight of the nearest male witnesses. It was said that the pirate himself seemed amused by this contest over his affections. In a valediction rendered through an interpreter, he assured the two girls that he loved them both to equal degree, a sentiment that stirred the crowd to murmurs of both grudging approbation and high skepticism. He gave one of the girls his gold earring and the other a finger ring set with a pearl in the shape of a skull. When he bequeathed his remaining credit at a cantina called Las Sirenas toward as many drinks as it would buy for the regular patrons of that establishment, there were loud cheers of “Viva el capitán!” from the corner of the plaza where that disreputable bunch was assembled.

He declined a blindfold and stood smoking a cigar, an insouciant thumb hooked in his belt, as the fusiliers took aim. At the muskets’ discharge, a squall of birds burst from the trees and a slow blue cloud of powdersmoke ascended after them. The officer in charge of the execution—a young lieutenant named Montenegro—delivered the customary coup de grâce pistolshot to the head. Then unsheathed his saber and with an expert slash decapitated the corpse.

The head was taken at once to the yellow-rock fortress of San Juan de Ulúa at the mouth of the harbor and placed on a tower pike in warning to all the city and every passing ship. The body was borne off in the donkey cart, and onlookers made the sign of the cross as it passed them on its way to the graveyard. And the two women who h

ad fought over him were not the only ones to dip their skirt hems in the blood puddled in the cobbles.

He was buried in the low-lying cemetery at the south end of the city. He had arranged for a marble headstone engraved with his name and ad vivum praedo. But within a week of his interment the marker was stolen by persons unknown.

On its high vantage over the harbor, the head blackened and was fed upon by birds and over time reduced to bare yellow bone with a .54-caliber hole in the parietal and an unremitting grin. The skull disappeared in the next hurricane, and the floodwaters forced open his grave and carried his bones to the sea.

PART ONE

HENRY MORGAN WOLFE m HEDDA JULIET BLAKE

1 Roger Blake Wolfe ______________ 2 Harrison Augustus

m Mary Margaret Parham

1 John Roger

m Elizabeth Anne Bartlett

1 John Samuel

2 Samuel Thomas

m María Palomina Blanco

1 Gloria Tomasina

2 Bruno Tomás

3 Sofía Reina

MARY MARGARET

AND THE GEMINI

The twin sons of Roger Blake Wolfe were born in late May under the apt sign of Gemini. Mary Margaret named them Samuel Thomas—the elder by three minutes—and John Roger. She and the boys lived with her widower father, John Thomas Parham, in a flat above his Portsmouth tavern, where she tended tables every night. It was a waterfront pub catering to a seaman trade, Mr Parham himself having been thirteen years a merchant officer before a shipboard mishap left him crippled of foot and permanently dependent on a crutch. Except for the first six weeks of her marriage, during which she and Captain Wolfe lived in a rented cottage, the tavern was the only home Mary Margaret had ever known or would. Only nineteen years old when widowed, she would afterward not lack for suitors but she would not marry again. As in the case of Roger Blake Wolfe, no picture of her would pass down through the generations, but her sons would describe her to their children as blue-eyed and slender, with pale brown hair she liked to wear in a braid down her back.

From the time of their early childhood the twins were curious about their father and now and again questioned Mary Margaret about him. Beyond telling them he had been a merchant ship captain and was lost at sea, she was disinclined to discuss him and was skilled at changing the subject. Both her reticence and her falsehoods were rooted in a sense of disgrace. She had not been able to surmount her angry shame over his desertion of her and their unborn children. A shame made all the worse after he had been gone for a year and a half and she received a letter from the British Embassy apprising her that her husband and British subject Roger Blake Wolfe, a captain of pirates and fugitive from justice, had been convicted of murder by the Mexican government and duly executed in the city of Veracruz. The letter did not relate the particulars of his crime or the means of his execution nor disclose the disposition of his remains, but she did not care to know any of those details. She wept for days in sorrowful and furious mortification. How could the man she loved so dearly have done such dreadful things? How was it possible she had loved a man so different in truth from what he had seemed to her? What other lies had he told her? The more she pondered these questions the more the very notion of love did baffle her.

She demanded her father’s promise not to tell her sons of Roger’s criminal occupation and ignoble death, and because he was sympathetic to her sentiments Mr Parham so promised. But although he did not say so, he believed she was in error to keep the truth from the twins. He was not so shocked as his daughter by the news about Captain Wolfe. He’d had his hunch about the man from the start, having been acquainted with a number of men disposed to outlawry and having at times even conspired in a bit of furtive business with some of them. This minor criminality was but one secret Mr Parham had kept from his wife and daughter. Another was that his father had been Red Ned Kennedy, the notorious mankiller and highwayman. Mr Parham himself had been unaware of his true paternity until after his mother died of the consumption when he was twelve and he was taken in by her old-maid sister. One day in a fit of meanness the aunt told him all about his nefarious father. “Hanged your pa was,” she told him, “in the public square at Kittery in the glorious year of ‘76, not six months after your birth. Your poor mam so wanting to spare ye the dishonor of him, God pity her, that she quit his name and took back our own. Oh, she thought she had herself a prize, she did, when she married that one with his easy smile and blarney and his promises to be a lawful man. And just look what came of it. Heartbreak and shame and an early widowhood. I’d a thousand times choose to have no man a-tall than be wed to a blackguard like him.” Young Mr Parham had affected a woeful disillusionment in his father in order to satisfy his aunt’s righteousness and thereby ease the temper of his stay with her until he was of age to go to sea. But he would all his life harbor a secret pride in a sire who had been so feared in his time, and the only regret he’d ever had in being son to Red Ned Kennedy was that he himself was not more like him. He thought his grandsons might feel the same way to know their own pa had been a “gentleman of fortune,” as the phrase of the day had it. Still, he knew better than to say so to Mary Margaret, who would certainly not agree nor even care to hear it.

But as the twins grew older their entreaties about their father became more insistent and difficult for Mary Margaret to deflect. She knew she could not go on refusing them but her heart remained a divided country in its feelings for her husband and she was uncertain of what to tell them. The boys were eleven when she at last capitulated to their appeals—and little by little, over the months, she acquainted them with Roger Blake Wolfe as she had known him. And in the process of so doing, she discovered that he yet held a greater claim on the sunny south of her heart than on its frosty north. Still, she never spoke of him to her sons by any name other than “your father,” “Captain Wolfe,” or simply “the captain.” Nor did she soon recant her falsehoods about his true vocation and manner of demise. And her accounts to them omitted of course many private particulars.

She met Roger Blake Wolfe on a summer eve when he came into the tavern for a mug of ale and dish of sausage. Dozens of sailors had wooed Mary Margaret in vain but with Captain Wolfe’s first smile she was smitten. He was not tall but carried himself as a tall man. He wore a close pointed beard and his black hair and hazel eyes would be replicated in his sons. So too his cocky grin. He began showing up at the tavern every night and each time she caught sight of him her breath deepened. He gladdened her. Made her laugh. Made her blush and feel warm with his compliments. His speech was tinged with the brogue of his Irish da. He was the only one she ever permitted to call her Maggie. She had known him barely two weeks the first time she sneaked out her window late one night to rendezvous in a moonlit copse above the harbor. She was seventeen. He was her first lover and her last.

Mr Parham too had taken a shine to the captain and when Mary Margaret, after barely two months’ society with the man, told her father they were in love and wanted to marry right away, he did not object. The next day he received Captain Wolfe at home and granted his request for his daughter’s hand. Mary Margaret was pleased but had expected resistance. Ever since her childhood both her father and her mother, a comely and lettered woman who died when Mary Margaret was twelve, had many times warned her about sailors as a breed not prone to cleave close to the hearth. Her father’s ready acceptance of the marriage convinced her he knew the real reason for her haste.

Her conviction was correct. Mr Parham had easily intuited Mary Margaret’s compelling condition and knew it was not the less compelling for being as old as morality and as common as cliché. Given that the usual course of sailors in such a state of affairs was to abandon the girl to her shameful fate, the real surprise to Mr Parham was Captain Wolfe’s willingness to marry Mary Margaret. It was testimony to the man’s honor that he would not forsake mother and child to the disrepute of bastardy. But while Mr Parham had no doubt of his daughter’s unreserved love for the captain,

he knew the captain’s love for her was of a different kind and that probably sooner rather than later the man could not help but break her heart.

On a crisp afternoon in early October they were wed in a maritime chapel overlooking Portsmouth Bay. The next six weeks were the happiest of Mary Margaret’s life. The captain was only twice absent from home and for only a few days each time, once to Gloucester and once to Portland, on business which he did not confide and about which she did not inquire. He had told her little of his past, saying there was little enough to tell. His Irish father a boat builder by trade, his English mother a beauty with a hearty laugh, both of them killed in a house fire when he was a child, and then a London orphanage until he ran away to sea. This bare synopsis was ample to her, as the man himself was her absorption. She liked to watch the play of his form as he axed cordwood, to see his enjoyment in meals of her making, to feel his fingers loosing her hair from its braid, to wake before him early of a morning and watch him still at sleep. To share in his love of dancing. Among her most joyful memories were those of high-stepping with him to the fiddles and pipes on a dancehall Saturday night. Sometimes when he was full of drink he would sing humorous bawdy songs and she would laugh even as she admonished him to mind his manners. He was a man of wit and easy laughter, she told her sons, and had a gift for telling a tale.

“Was he a good fighter?” Samuel Thomas once asked, his eyes avid. And was puzzled by the melancholic look his mother fixed upon him. Then she sighed and said yes, the captain could surely fight. She had witnessed the proof of it one busy evening in the tavern. There was a sudden commotion at the rear of the room and she looked over there to see a large man speaking angrily and pointing a finger in the captain’s face, but she could not hear his words for the clamor of the crowd forming about them. Then she had to stand on a chair to see—and she nearly cried out at the sight of the man brandishing a long-bladed knife such as the shark-fishers used, and the captain barehanded. The circle of spectators moved across the floor with the two men as the sharker advanced on the captain with vicious swipes of the knife. She mimicked the sharker’s action—swish swish swish—and how the captain hopped rearward with his arms outflinging at each pass of the blade. Her eyes were brighter than she knew as she reenacted the fight for her sons, who were spellbound. Then a heavy tankard came to the captain’s hand, and in his next sidestep of the knife he struck the sharker a terrific blow to the head, staggering him. Then hit him again and knocked him stunned and bloody-faced to the floor. He kicked away the knife and stood over him with an easy smile and the room thundered with bellows to finish him, finish him! The man was on all fours when the captain clubbed him on the crown with the tankard and he buckled like a hammered beef. The walls shook with cheering. The unconscious sharker was dragged away by the heels to be deposited in the alley. The captain grinned whitely in the blackness of his beard and fired a cigar. Then his eyes found her still atop the chair and her hand to her mouth. And he winked.

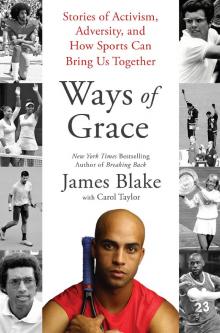

Ways of Grace

Ways of Grace The Widow Bereft

The Widow Bereft Country of the Bad Wolfes

Country of the Bad Wolfes