- Home

- James Blake

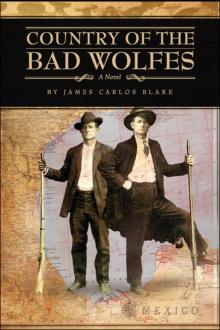

Country of the Bad Wolfes Page 13

Country of the Bad Wolfes Read online

Page 13

PART TWO

BUENAVENTURA

Sombra Verde was very different in geographical character from the hacienda Corazón de la Virgen that they had visited some years earlier, but the estates were similar in organization and amenities. It was a self-sustaining settlement, feeding off its cornfields and orchards, its pig farms and chicken roosts and dairy, its beef cattle that was processed into meat at the downriver slaughterhouse. The compound was centered by a plaza with a fountain and a church, a main store, a trio of stables with a large adjoining corral. Also fronting the plaza was the walled enclave containing the casa grande. Though it had three stories, the compact design of the house made it small by hacienda standards, but it was still larger than either of the mansions in which Elizabeth Anne had been reared. It boasted all the usual facilities, including an armory, though few of the arms had seen use since the days of the Valledolids, who had kept in hire a dozen pistoleros, while the Montenegros could scarcely afford to maintain half that many. John Roger told these men their service was no longer required and paid them a discharge bonus and they shrugged and left. At Elizabeth Anne’s suggestion he renamed the estate Buenaventura de la Espada, which over time would be simplified in casual reference to Buenaventura. All of the casa grande’s furniture had been shipped from Spain for the Valledolids, and the Wolfes chose to keep most of it. Elizabeth Anne was especially delighted by the piano in the salon, though it was in bad need of tuning. The only item of furniture they rejected was the bed in their private chamber. It was a mammoth thing of polished mahogany and a feather mattress, but they would not lie where Montenegro had lain. John Roger had the mattress burned and a bookcase made from the fine wood frame. The walls of the residence were cleared of Montenegro portraits and they too went into a fire. He had the bones in every Montenegro grave exhumed from the little cemetery adjoining the casa grande garden and reburied in the communal graveyard of the neighboring village of Santa Rosalba. As the Montenegros had done with the bones of the Valledolids.

Every morning, before breakfast—always prepared for them by Josefina herself, though she now had several helpers in the kitchen—they took coffee on a third-floor balcony from which they could see the huts of Santa Rosalba and its cornfield and the orange sun swelling up from the far reach of the forest. The air cool and redolent of wet foliage. The cock crowings loud. Santa Rosalba was one of two villages on the estate. The other, Agua Negra, was up in the foothills, next to the coffee farm.

They liked to watch the hacienda plaza come to life. The workers from the village arriving at the gate. The head-scarfed women scurrying to the church bell’s call to early mass. Storekeepers dampening and sweeping the sidewalk in front of their shops. Gardeners wheeling their barrows full of tools, the smithy stoking his furnace just inside the stable door, the wranglers at the corral rails. The rising odors of cookfires and dust. At day’s end John Roger and Elizabeth Anne would sit on the other side of the house and watch the sun lower into the western sierras. This balcony overlooked the hacienda’s main docks on the Río Perdido, the water the color of copper in the late afternoon light. Herons stalked the shallows along the bank. Roosting parrots screeched in the trees. Fishermen moored their dugouts and unloaded their night’s catch of fish and eels and turtles.

After breakfast, it was John Roger’s daily ritual to meet with his estate manager—the mayordomo, Reynaldo Espinosa de la Santa Cruz—and review the day’s schedule and discuss any business of importance. While a patrón’s authority was absolute, the chief administrator on most haciendas, the man to whom all lesser supervisors had to answer directly, was the mayordomo. A slim courtly man with a black spade beard and only three years John Roger’s senior, Reynaldo had been the mayordomo for ten years, the latest in a continuous line of Espinosas to have administered the hacienda since its founding in the sixteenth century. His family had served many Valledolid patrones and two Montenegros. He and his wife and children lived in a spacious residence within the casa grande enclave. He had welcomed John Roger with such warm respect that it seemed needless to ask how he felt about the change in owners. Given the man’s knowledge of the hacienda and his expertise in its operation, John Roger naturally wanted him to stay on as his mayordomo, and he was relieved when Reynaldo said, I would be honored to remain in your service, Don Juan.

They met every morning of the week but Sunday, and after their conference John Roger would usually devote himself to reviewing Trade Wind accounts. On Saturdays, after Reynaldo meted out the workers’ weekly wages, paying them one-fourth in silver specie and the rest in script redeemable at the hacienda store, John Roger would conduct the weekly court session in the compound plaza. He sat at a table in the shade of a tree and settled grievances large and small concerning hacienda residents. Most cases were trivial contentions of property between neighbors—a dispute over the rightful ownership of a stray pig, or of the eggs laid by someone’s hen in someone else’s yard. But at times he was presented with more serious issues. A petition for retribution by a man whose young son was mauled by another man’s dog. A bridegroom’s allegation of fraud whereby his bride in an arranged marriage proved not to be the virgin he had been assured she was. The judicial responsibility was one of the most important of a patrón, and John Roger fulfilled it well. He viewed the Saturday courts as a recurrent test of his reasoning and principles of justice, and his judgments earned him wide respect as a man both wise and fair. Elizabeth Anne greatly enjoyed these court sessions and never failed to attend them. It pleased her that in almost every case John Roger’s ruling was such as she herself would have made. She confessed to him that back in their Concord days she’d had a covert hope he would one day run for mayor, as she was convinced he would make a fine one. But as patrón of Buenaventura, he had the full powers of an entire government—executive, legislative, and judicial. “Why, it’s better than being governor of New Hampshire!” she said. He laughed and said he believed it was.

During their first months in residence at the hacienda, they sometimes made the daylong journey to Veracruz to spend a few days, but by the end of their first year as hacendados they rarely went to town, and the only times they saw their friends were when they came to Buenaventura. Charles Patterson and Amos Bentley would come to the hacienda on every other Friday for a visit of a day or two. They would bring the most recent editions of American newspapers and their own news of the city and of the country at large. Amos would deliver the latest Trade Wind paperwork for John Roger’s review and collect the records he had examined over the previous fortnight. In the warmest weather they would all don bathing costumes and cool off in the shallow concrete pool in the garden arbor, and after dining in the company of Elizabeth Anne the men would repair to the den for whiskey and cigars and would converse into the night.

Also in that first year a strange and wondrous thing happened—the coffee farm rejuvenated and produced the largest harvest in its history. The next season’s yield would be even greater. Such bountifulness would persist for a long time to come and earn John Roger yet another fortune. There was no rational explanation for the farm’s robust revival after twenty years of meager output, but the villagers believed the farm’s plight had been caused by the legendary curse of Martín Valledolid, and that the cessation of Montenegro proprietorship had ended the curse. But more than that, they believed Don Juan and Doña Isabel were favored by God, and so the hacienda was now divinely blessed.

When Reynaldo told the Wolfes of these popular explanations for the farm’s renewed fertility, they were amused, although Elizabeth Anne thought the villagers could be right. How else explain such a miraculous turn of good fortune except by divine favor? Reynaldo smiled on her like a fond uncle and said that whatever the reason for such fecundity, it had even reached into his own house. His wife had before informed him just the night that she was in the family way.

The Wolfes were thrilled. They knew Reynaldo’s sad history of parenthood. Of the twelve children his wife had born one after the other,

nine had died of illness or by accident before their tenth birthday, leaving the family with a sole son, Mauricio, and two daughters. Though Reynaldo and his wife both wanted another son, she had not conceived for the past three years. Until now.

You see! Elizabeth Anne cried. You see how blessed we all are? She hugged Reynaldo in congratulations and said she knew he was hoping for a boy and asked what name he had chosen if it should be.

Alfredo, Reynaldo said.

ENSENADA DE ISABEL

They made a gradual acquaintance with the entire hacienda, exploring it by buggy, on horseback, in canoe, afoot, until they’d seen all of it except for a section of rain forest along the lower river—which, so far as anyone knew, had never been penetrated even by Indians—and no part of the estate was dearer to them than its little cove at the mouth of the Río Perdido some twelve miles below the compound as the crow flew. The route to get there, however, was hardly as direct as crow flight. And although the river snaked through the jungle all the way to the coast, it was of little use for downriver transport because of the rapids that began just four miles below the compound docks, a stretch of whitewater so daunting that not even the hacienda’s most able boatmen would brave them. A few had tried it in years past and had never been seen again. It was supposed that the rapids ran for many miles, but no one knew for sure.

The first time John Roger and Elizabeth Anne went to the cove, they left the compound three hours before dawn and were conveyed by a lantern-lit raft through the river darkness to a small dockage about a half mile above the rapids. Even at that distance they could faintly hear the whitewater rush. From this lower landing they proceeded by ox wagon, with supplies and camping gear, on a narrow trail that had been hacked out many years before by the crew of fishermen whose periodic duty it had been to provide Hernán Montenegro with the oysters and crabs and shrimp he cherished. Reynaldo the mayordomo knew of no one who had ever been to the cove but those fishing crews. The fishermen had praised the prettiness and the bounty of the place, but said that if they had had a choice they would rather forgo the rigors of getting there, and they wished Don Hernán had not had such a liking for shellfish. They would scoop oysters and net crabs and shrimp until they had sackfuls of each, then smoke the entire catch to preserve it for the return trip. And then one night, about a year before his death, Don Hernán had become violently sick after a meal of the smoked oysters. The servants tending to him could hardly believe the quantities of vomit and horrifically stinking shit he produced on that interminable night, and they thought it a wonder that he survived it. At daybreak he looked like he’d lost twenty pounds and was as sickly pale as wax. He never again ate shellfish of any form, and so far as Reynaldo knew, no one had been to the hacienda’s seashore since.

The track held close to the river’s meander and in places was so narrow the foliage brushed against both sides of the wagon as they swayed and tilted over the uneven ground. Both the driver and their guard were Indians, the guard riding behind on a burro. Both men armed with machetes and shotguns. Although the disorder of the Reform War had worsened the national plague of banditry, robbers were most unlikely in this jungle—but jaguars and wild boars and poisonous snakes were not. Under his leather jacket John Roger carried a .36-caliber Colt in a shoulder holster, and in Elizabeth Anne’s handbag was a .41-caliber derringer. To fend against the rage of mosquitoes they had covered their faces and necks and hands with a unguent of Josefina’s concoction that smelled so foul they questioned whether the mosquitoes might not be the lesser torment.

Under a high shadowing canopy of trees shrill with birds and monkeys, the air grew hotter and wetter, riper in its smells of vegetation. The light was an eerie green. John Roger had been fretful of Elizabeth Anne risking her health in such close heat, but she assured him she felt fine. It was his guess that in some places they were hardly more than ten yards from the river and never farther than twenty, but the undergrowth was so heavy that at no point did they get so much as a glimpse of the water. They might not have known the river was there but for the rumble of the rapids, which grew louder and louder until they were abreast of them for several miles in which the green air was misty with vapor and they had to raise their voices to be heard. He wanted to have a look, but to get near enough to the riverbank would have required an hour or more of hacking with machetes by all three men, an expense of valuable time they could not afford. And too, there was the matter of jaguars and boars and snakes. They pressed on, the roar of the rapids gradually diminishing back to a rumble, and after a while longer they heard only the river’s low hiss through the bankside reeds.

Near day’s end they emerged from the closing darkness of the river into the last afternoon light of the cove. It was an oval some eighty yards wide from the landward to the seaward side and half again that long from north to south. The trailhead was near the cove’s northwest end, within sight of the river mouth. The cove surface looked like a slightly warped mirror of green glass, much darker at this hour than it would be under the overhead sun. They could not see the inlet on the other side because it did not open directly to the gulf but lay between a pair of narrow and overlapping tongues of land parallel to the coastline and dense with coconut palms. The trees blocked their view of the ocean but they could hear the swash of small waves on the outer shore. On the cove’s landward side the jungle ended on a small bluff that sloped down onto a smooth white beach. The beach curved all the way around the south end of the cove and was askitter with crabs of red-and-blue.

“My God, it’s so beautiful,” Elizabeth Anne said. She pointed to the bluff. “Up there, Johnny, up there’s the place for a house.”

John Roger told the guard and driver to relax, and the two men settled themselves under a tree and began to roll cigarettes. He and Elizabeth Anne then took off their shoes and walked barefoot out on the beach, crabs sidling out of the way ahead of them. They went up the slope to the little bluff and found that although it was not quite high enough for them to see the gulf on the other side of the palms, there was a steady breeze that kept off the mosquitoes. John Roger agreed it was a fine spot to build a house.

They went back down to the beach and walked around to the other side of the cove and went through the palms and there the gulf was. As far as they could see to north and south a high wall of palms leaning to landward was fronted by a sand-and-rock beach barely ten yards wide at any point at this hour of ebb tide. The gentle waves rolled in low and crested as small breakers, spraying on the rocky shore and rushing over it in a foaming sheet and then running back out again.

They backtracked through the palms to the cove beach and headed for the inlet and before they got there the sand under their feet became stony ground. The inlet formed a pass less than fifteen feet wide and about fifteen yards long from its outer mouth to its inner one, both banks craggy with rocks. It looked about four feet deep at the ebb and John Roger guessed it would rise close to two feet at high tide. On the inland side of the pass the bottom grass leaned toward the cove with the incoming current but on the outer side where they stood the grass was pulled the other way by the current going out.

“See how the current makes an easy circuit all the way around?” John Roger said, gesturing with his arm. “But through this pass it moves pretty fast coming in and going out.” He picked up a coconut and dropped it into the water and it whipped away on the outgoing current and around the outer tongue of the inlet. It carried out into the gulf for about fifty feet before it slowed to an easy bobbing and began drifting toward the southward shore.

The outer mouth presented a difficult angle of approach from the open water. John Roger thought only expert hands might be able to sail a boat through this pass without either hitting the rocky projection of its outer tongue or veering into the leeward rocks. Elizabeth Anne grinned and said she was game whenever he was.

Because the inlet faced up the coast and its outer arm overlapped the inner one and was so thick with palms, it was impossible to see it from anywh

ere out on the gulf except if you were north of the inlet and very close to the shore, and even then you would have to be looking hard for it. “You could sail by within fifty yards and never see this opening,” John Roger said.

“Our own secret harbor,” Elizabeth Anne said. “I love it.”

He christened the cove Ensenada de Isabel and rued the lack of a flag to plant.

Josefina had supplied them with an oilskin sack of food—a stack of tortillas bundled in a damp cloth, a pouch of dried beef, two jugs of cooked beans, and a bag of oranges. In the last red light of day John Roger made a fire on the bluff and Elizabeth Anne invited the driver and guard to come and sup with them. The men had brought their own provisions and had made a campfire near the wagon, but they accepted the Wolfes’ invitation. After supper John Roger told them they could sleep in the wagon, and he and Elizabeth Anne went up on the bluff, up where the crabs did not go, and huddled on one blanket and covered themselves with another against the evening’s cool breeze.

He woke twice in the night, savoring the sea breeze, the crush of stars, the bronze gibbous moon low in the east. The feel of Lizzie snugged against him. The second time, just as he was about to doze off again, he heard her murmur, “This is heaven.” And next time woke to a radiant sunrise.

They got back to the compound after dark, and later that night, in the privacy of his office, John Roger took out the journal he had not opened in years and recorded his happy plans.

It took a year to build the house and improve the trail for getting to it. John Roger spent long periods encamped at the cove with the labor crews and supervising the construction. He had the wagon track lengthened from the river mouth to the landing at the hacienda compound and improved the trail the full length of its entire river-hugging wind through the jungle. Each time he came home for a visit he was leaner, harder of muscle, more darkly sunbrowned. After the first few months, he forwent shaving and his beard grew black and wild. Elizabeth Anne was roused by his brutish appearance. When she said he now looked more like a pirate than even her Uncle Richard, he affected a menacing leer and advanced on her, saying in low growl, “Arrgh, me captive beauty, it’s yer sweet flesh I’ll have for me sport”—and she let a gleeful cry as he tumbled her into bed. She loved the beard and asked him to keep it and she trimmed it for him. She missed him terribly in his absences and chafed at her long exclusion from her cherished cove. She pleaded to go back with him and swore she would not complain about living in a tent until the house was ready to move into. But he would not permit her to see it until it was completed.

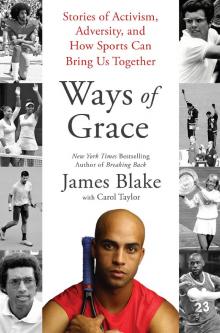

Ways of Grace

Ways of Grace The Widow Bereft

The Widow Bereft Country of the Bad Wolfes

Country of the Bad Wolfes